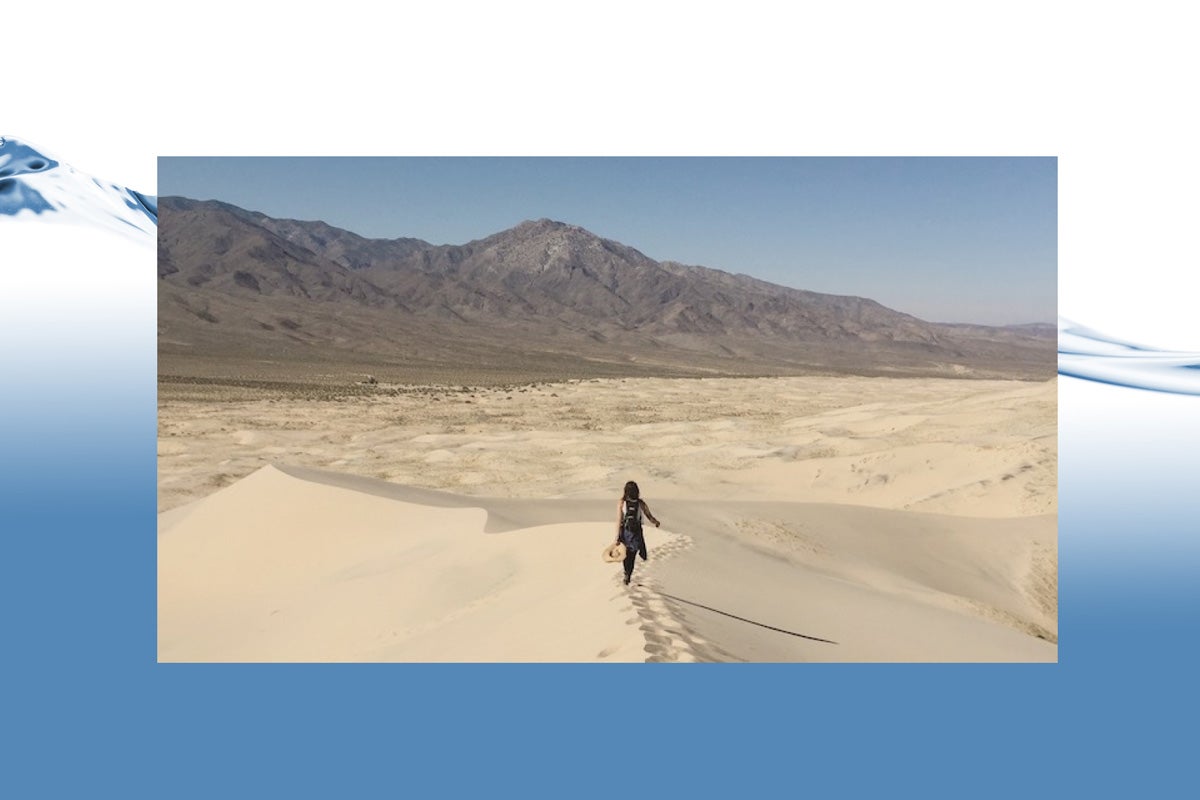

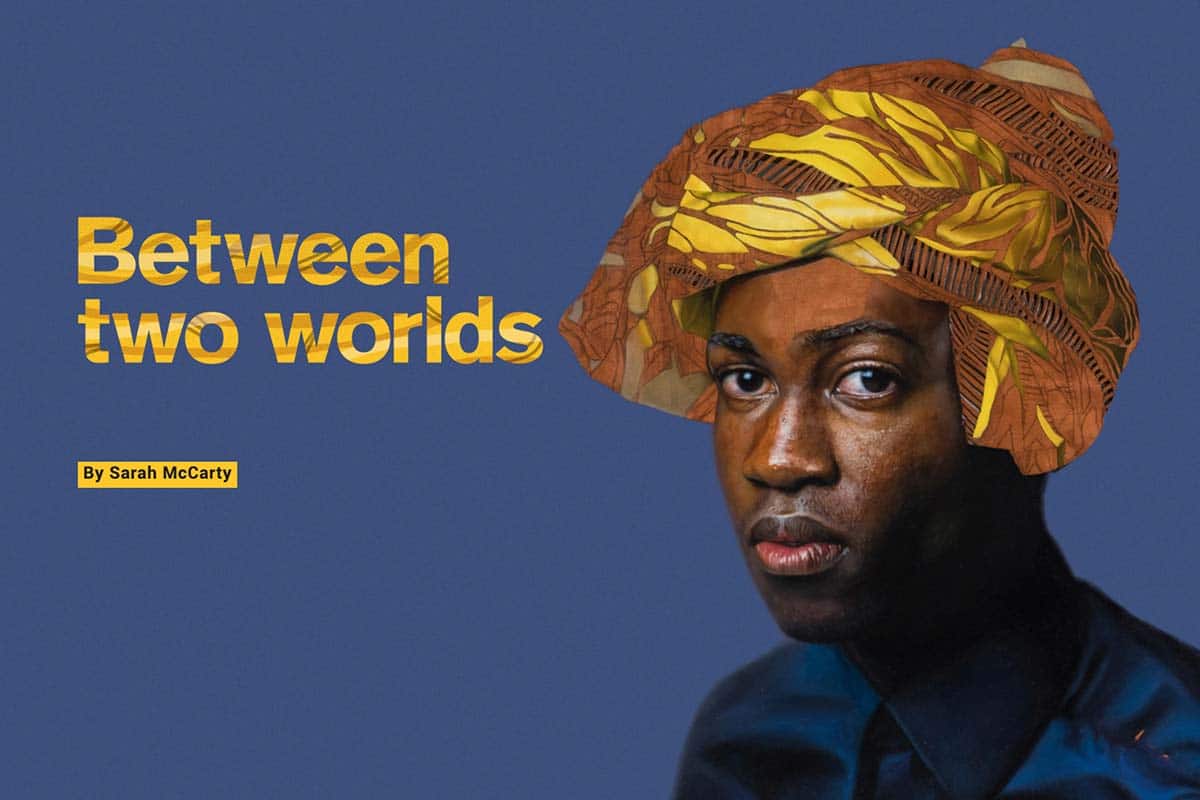

A MEMBER OF the Saddle Lake First Nation in Alberta, Wanda Dalla Costa was originally inspired to pursue architecture after spending seven years backpacking around the world. What began as a six-month adventure ended up taking her to almost 40 countries.Dalla Costa said she “fell in love with walking around in cities and the vitality of the indigenous architecture overseas; … ‘indigenous’ means everyone who’s trying to maintain their ancestral environment. For me it’s a broad definition … about built environments nurturing our cultural connections.”

When she returned to North America, she applied for a master’s degree in architecture at the University of Calgary.

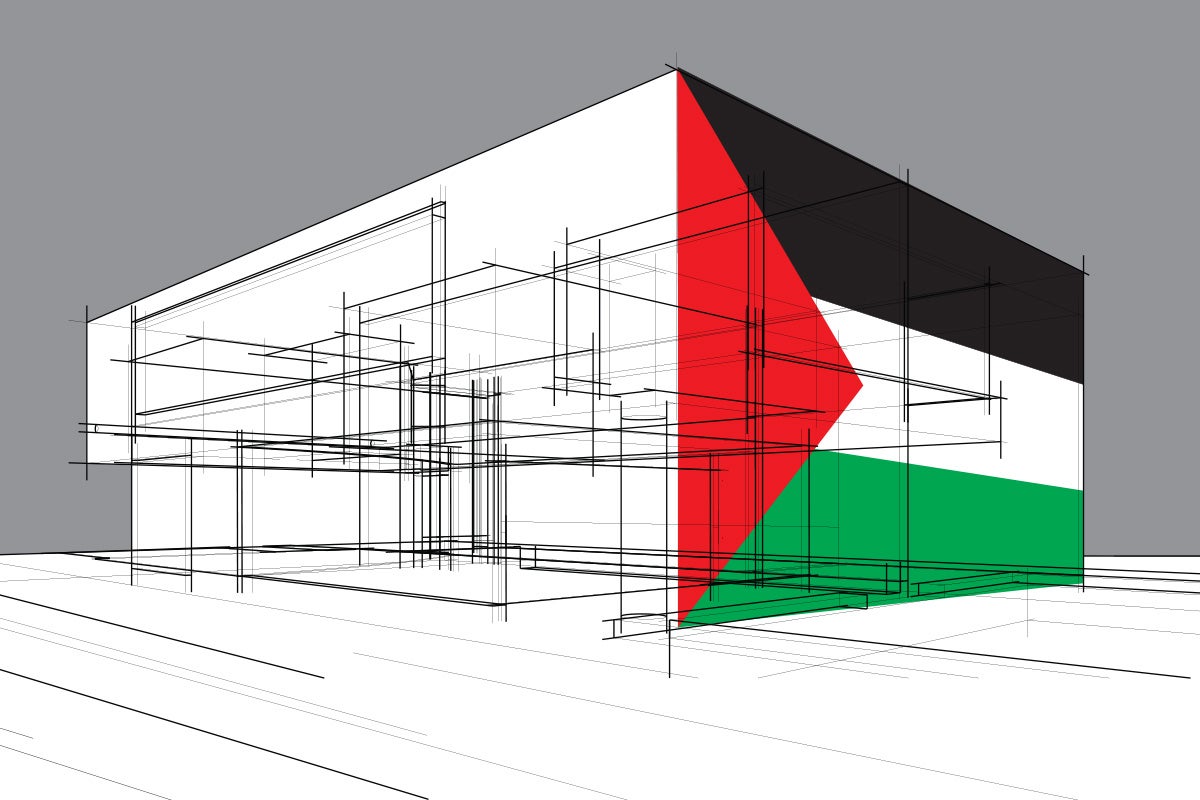

The question that drove her, she said, was this: “Why are we living in these boxes in the landscape that have no relation to our culture? The reservation is so divergent from the way we were traditionally so connected to our environment and to the land.”

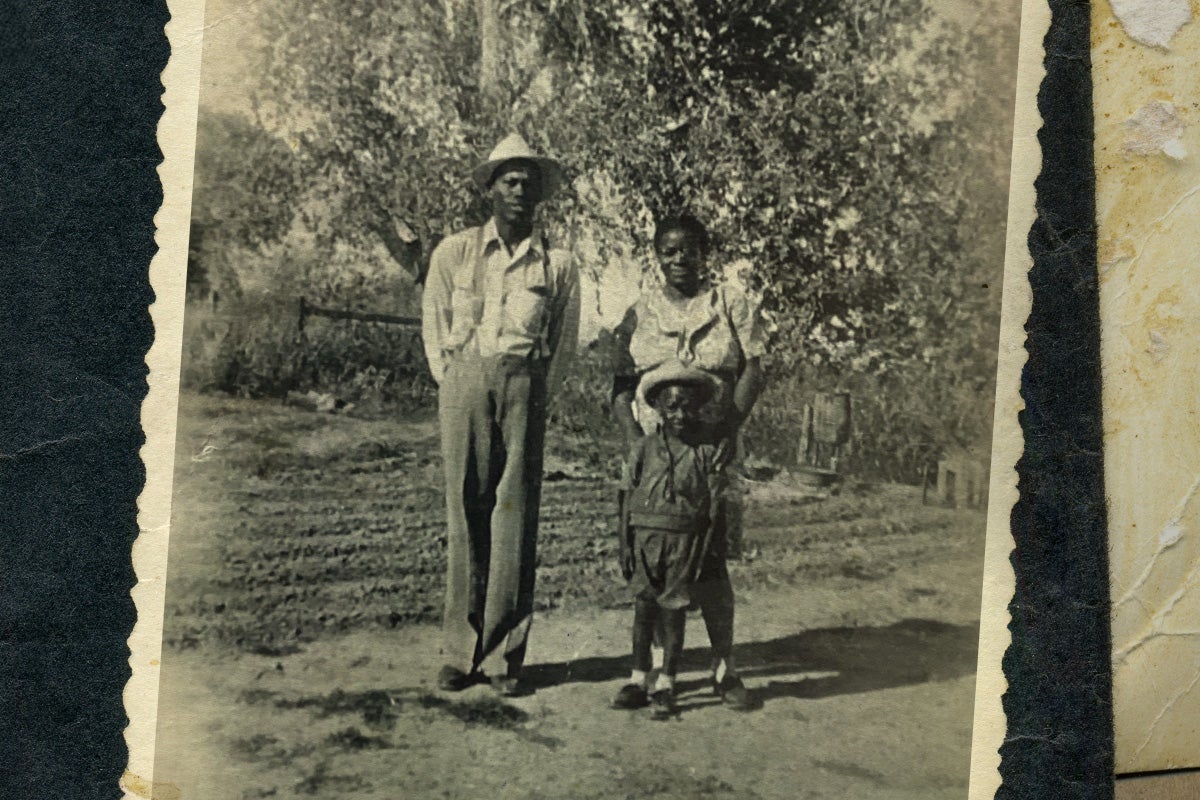

“My mom grew up on the reservation,” Dalla Costa said. “She was very tied into her culture growing up. We spent a lot of time on the rez. For me there’s a clear disconnect — when I got to architecture school, nobody was teaching (indigenous architecture); nobody understood it.”

In 2017, after nearly two decades working with indigenous communities in North America, Dalla Costa became Herberger Institute’s fifth Institute Professor. She also acts as an advisor on issues of creative placemaking and as an advisor on the Herberger Institute’s Projecting All Voices initiative. Her position at ASU is a cross-appointment between The Design School and the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

“Wanda is an architect who thinks deeply about the social and cultural aspects of place,” said Herberger Institute Dean Steven J. Tepper. “She has developed a practice that fully engages community partners and honors local knowledge and traditions.”

The first First Nation’s woman to become an architect in Canada, Dalla Costa is one of the North America’s leading authorities on indigenous architecture, with expertise in culturally responsive design, sustainable-affordable housing, climatic resiliency in architecture, and built environments as a teaching tool for traditional knowledge.

Dalla Costa’s first priority, she says, is mentoring students. She hopes to start an indigenous design collaborative at ASU.

“I do a lot of projects with tribal communities,” Dalla Costa said. “In the courses I teach, I bring students out to the reservation, and the students design or plan or build something for a tribal client. I think it’s a powerful way to teach.”

Ideally, she said, “there would be a system or a mechanism in place that could help think through a best approach, a best practice for each project we’re embarking on. It would be a resource center, and it would be a center of mentorship for those up and coming in this field, creating the support system for this work to come alive at ASU.”