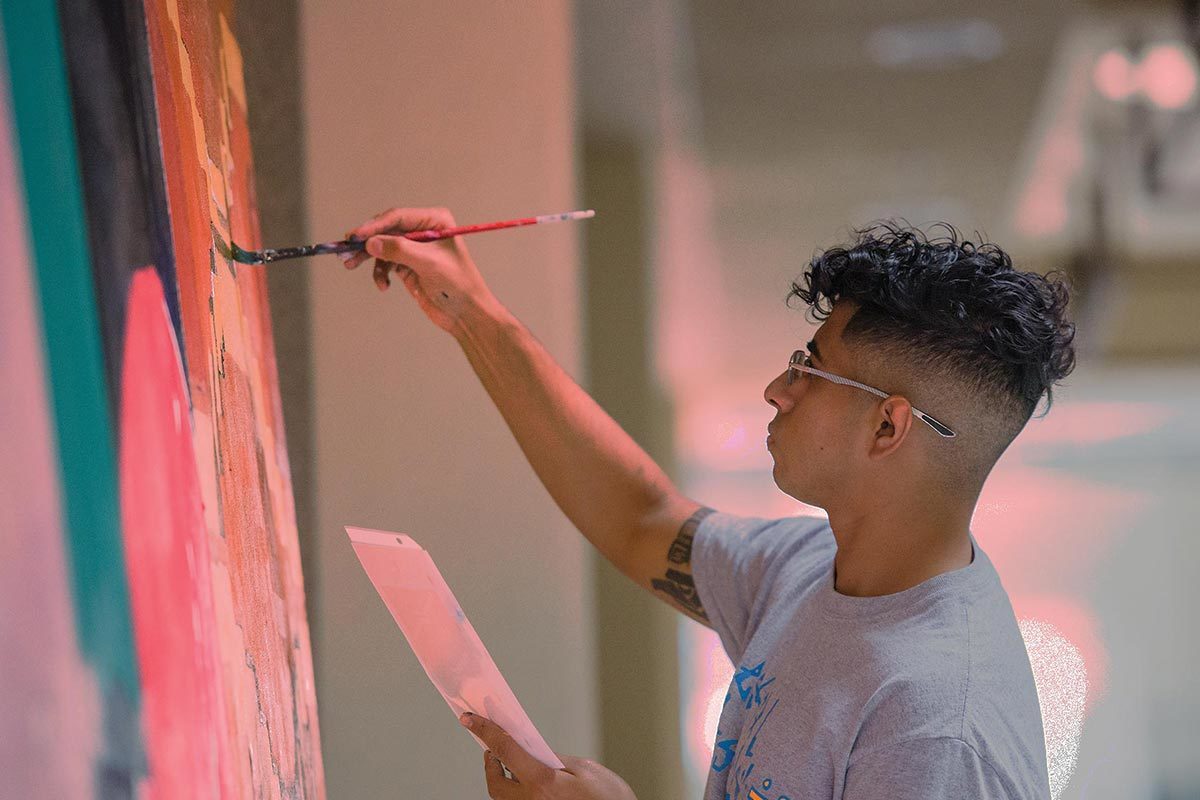

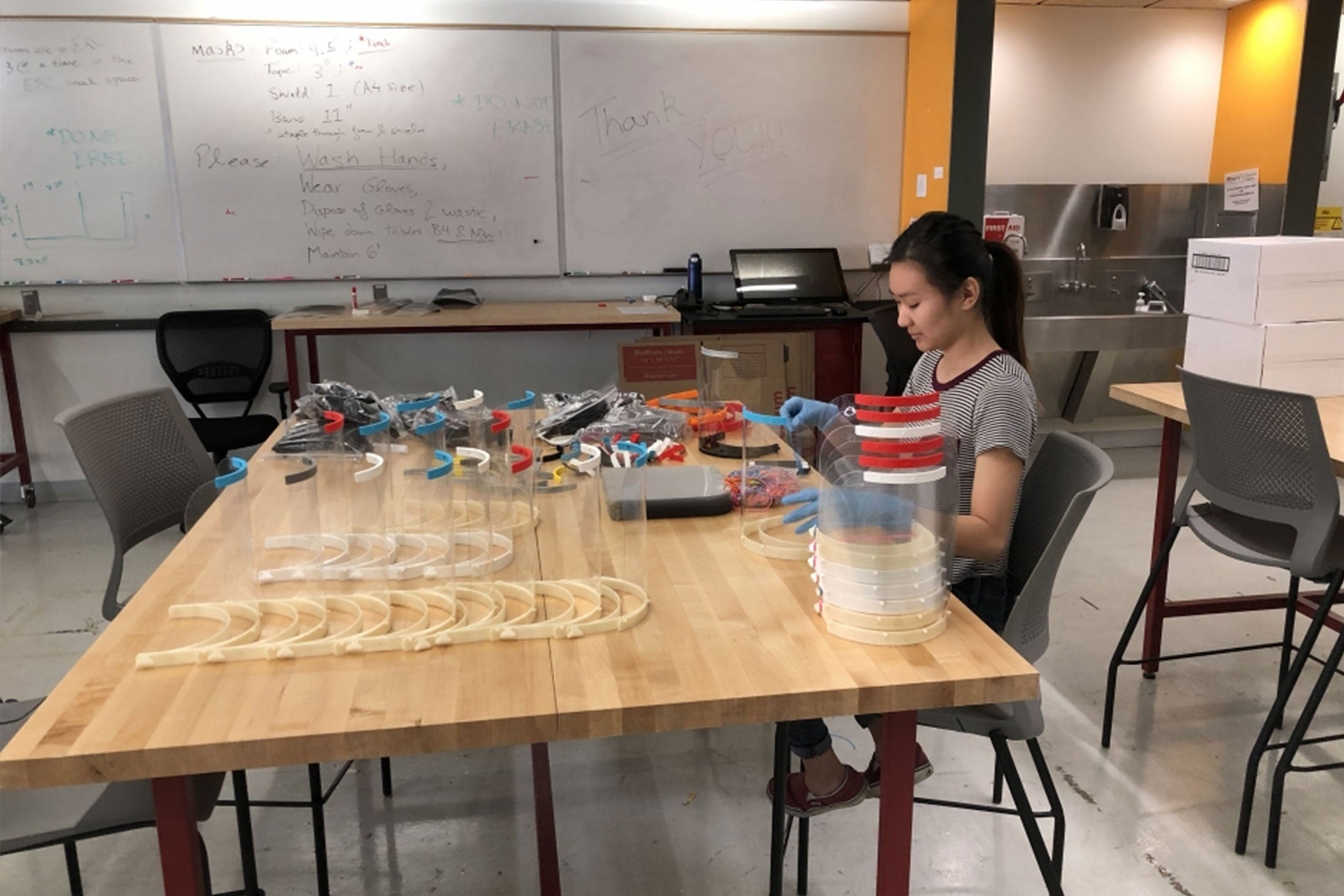

In April, Arizona State University responded to the coronavirus crisis by ramping up a massive initiative to design, produce and distribute critically needed personal protective equipment and other medical supplies.

Not only is ASU continuously fabricating gear to protect health care workers, it’s also leveraging its size and speed to activate the entire community to fulfill the need.

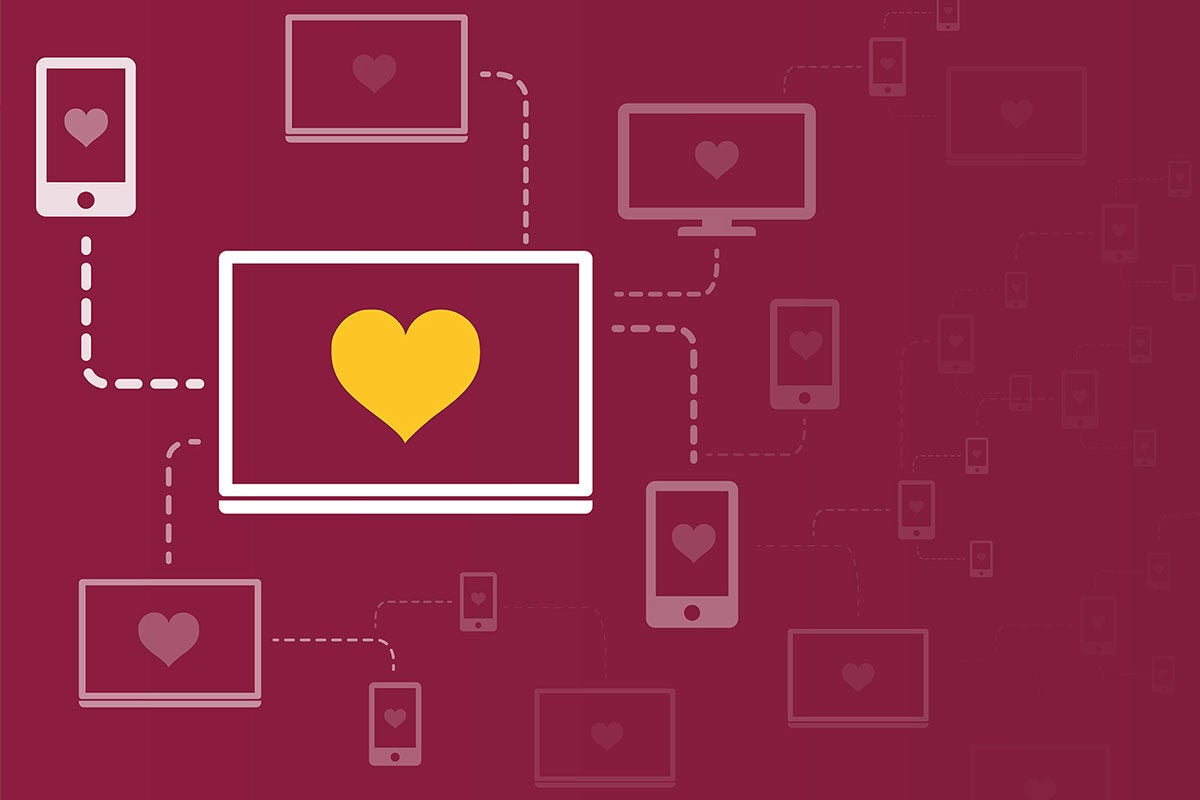

ASU unveiled a new web site called the PPE Response Network that links university and community resources such as 3D printers and sewing equipment to hospitals that need face shields, medical gowns and nasal swabs, and then tracks the lifesaving equipment from creation until it’s being used to help patients.

“Our goal here is to build a cohesive tool that Arizona’s community can use around the rapid development of personal protective equipment,” said Mark Naufel, executive director of ASU’s Luminosity Lab, which is leading the effort.

Other units involved in the PPE Response Network include the School of Art; the School of Arts, Media and Engineering; the Polytechnic School; the School for Engineering of Matter, Transport and Energy; and the Biodesign Institute, among many others.

Already the network has worked with a number of organizations — Banner Health, Equality Health, Dignity Health, HonorHealth and Arizona Academy of Family Physicians, among others — to get their equipment needs registered and underway. The team is working hard to reach and connect health care providers of all sizes, from small provider groups to larger health care systems.