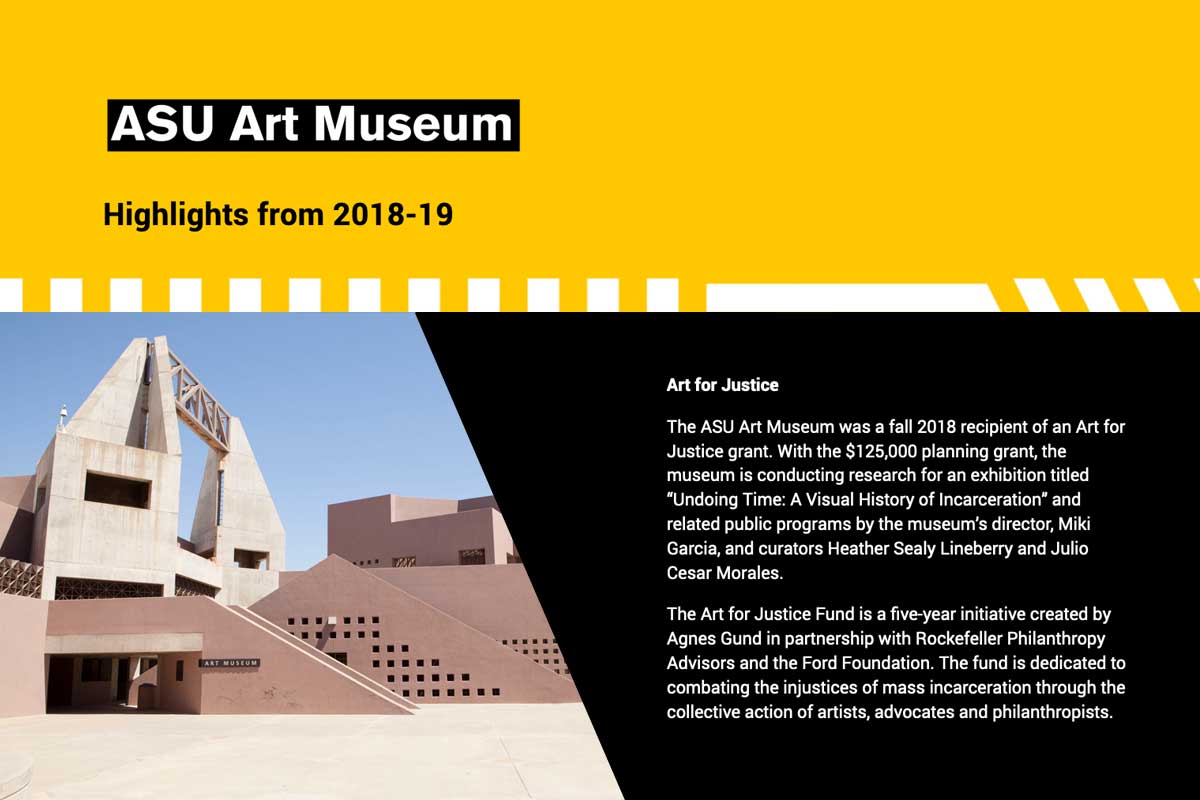

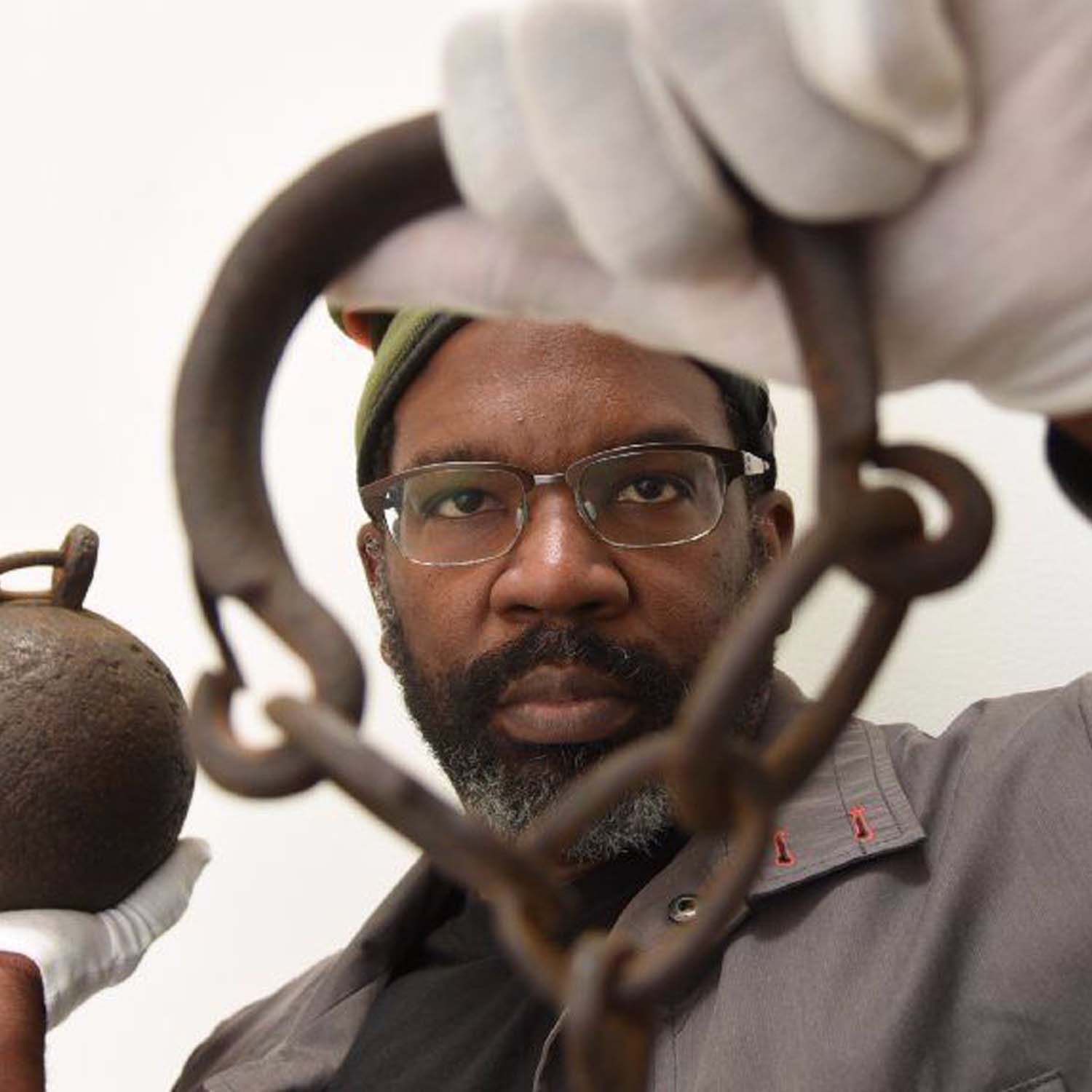

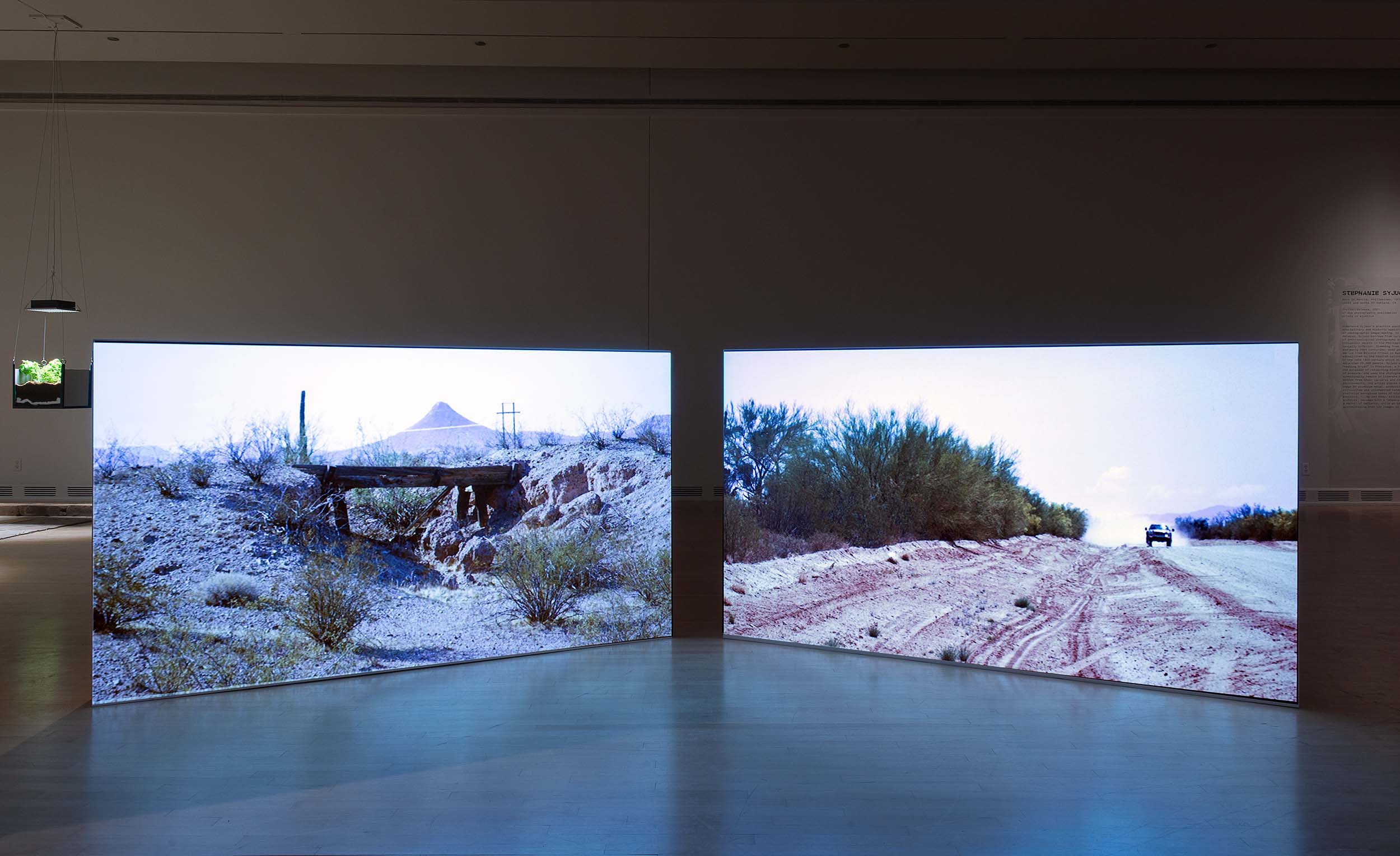

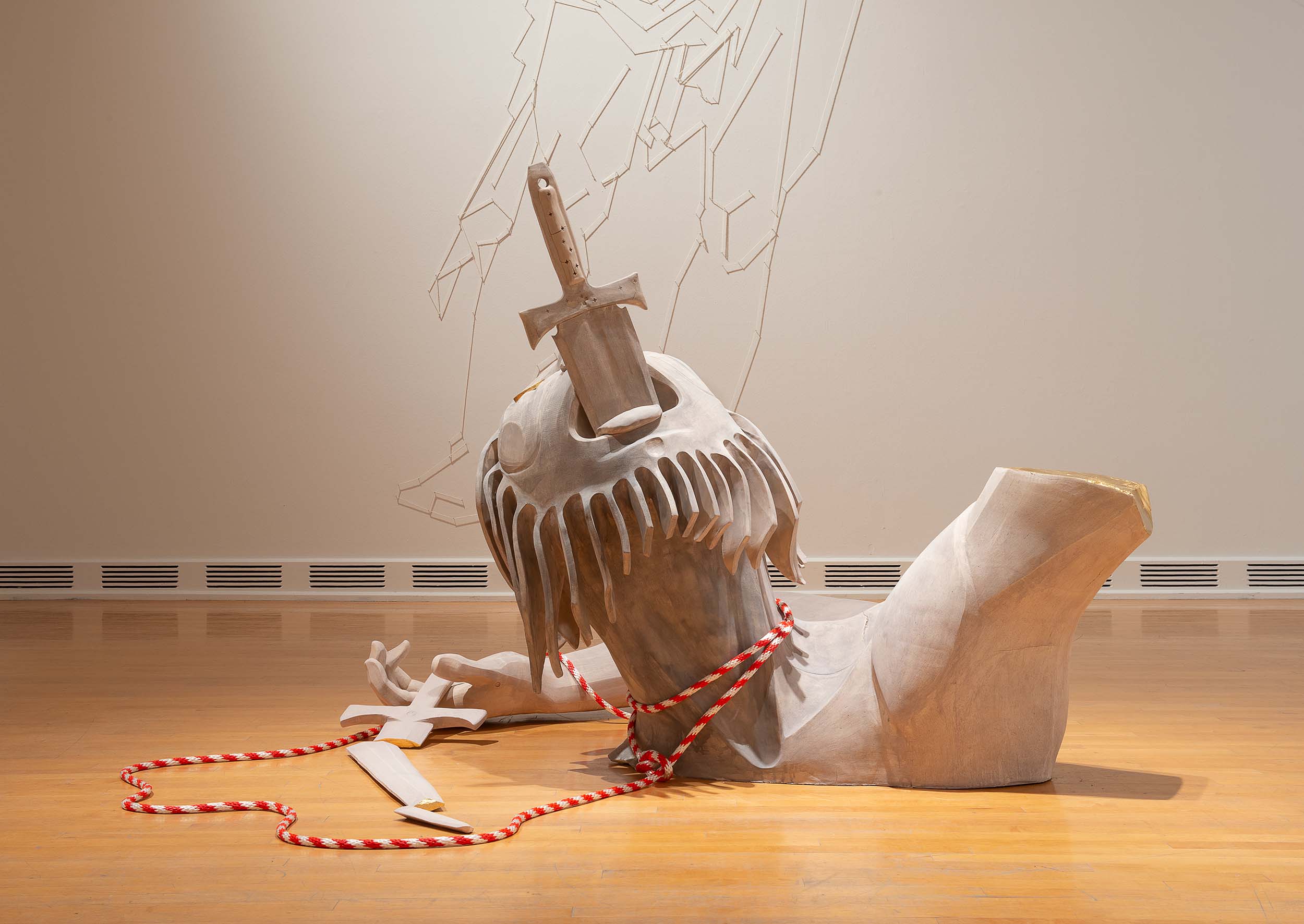

The ASU Art Museum recently opened a groundbreaking exhibition in which 12 artists have created new works that explore the tragedy of mass incarceration.

“Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration” will run through Feb. 12. The show is the first one ever to take over the entire ASU Art Museum space.

The museum began working on the project three years ago when it received a planning grant from the Art for Justice Fund, according to Miki Garcia, director of the museum. In August 2020, the museum announced it received another Art for Justice grant for $250,000 to help implement the exhibition.

“I would say that this is the most ambitious and largest exhibition the museum has ever endeavored, and it’s in the midst of Black Lives Matter protests and of the museum seeing itself as a champion of the community’s well-being,” she said.

“We wanted to take a risk and say, ‘This is what we stand for — putting artists in the midst of these urgent conversations.’”

The exhibit, which is kicking off with a celebration and panel discussion on Friday, will include never-before-seen sculpture, film, paintings and drawings from the artists, whose work combines history, research and storytelling. They are: Carolina Aranibar-Fernández, Juan Brenner, Raven Chacon, Sandra de la Loza, Ashley Hunt, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Michael Rohd, Paul Rucker, Xaviera Simmons, Stephanie Syjuco, Vincent Valdez and Mario Ybarra Jr.

Aranibar-Fernández is the current Race, Arts and Democracy Fellow in the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at ASU. Her mixed-media installation is called “Multi-ples Capos (Multiple Layers)” and includes sculpture, sound and organic plants.

“I was thinking a lot about displacement of land through incarceration but also what happens to the multiple layers and histories of the land that we see and what we don’t see,” she said.

Her installation includes a small wall out of adobe bricks made in Arizona, with some covered in gold leaf.

“Gold is an extracted resource but also a form of power,” she said.

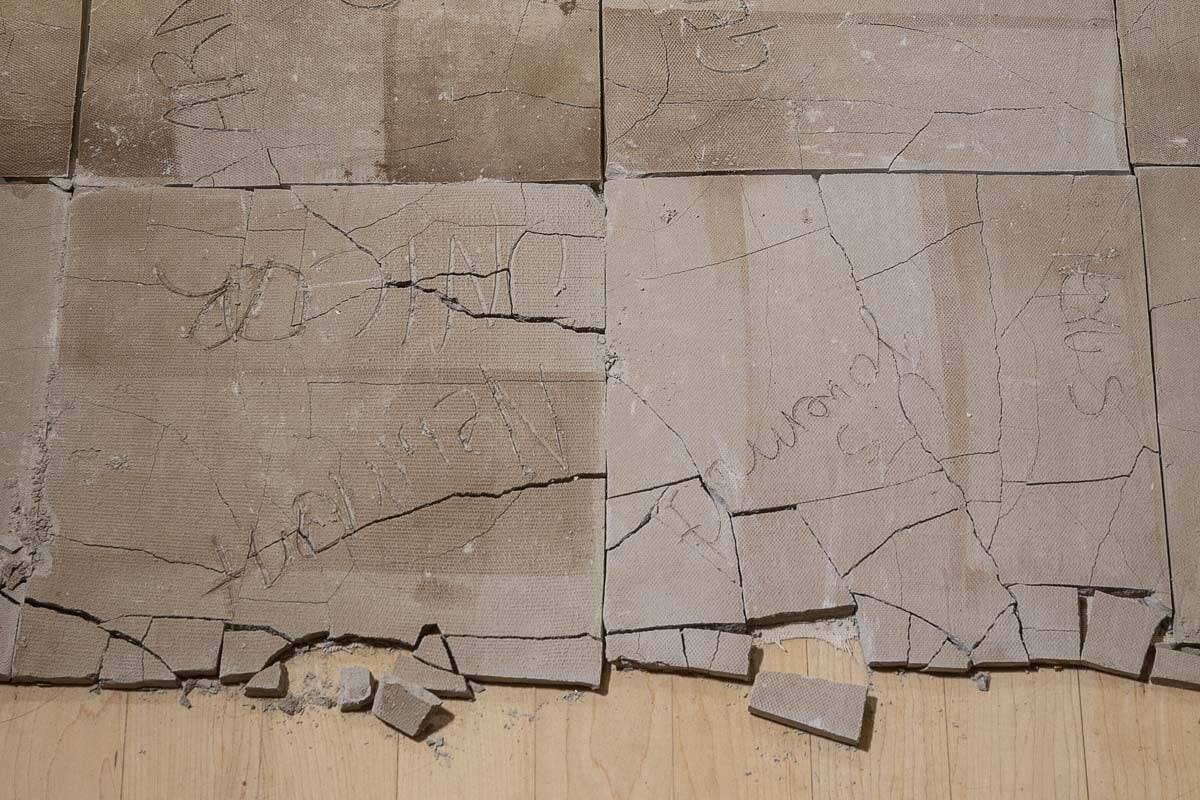

Aranibar-Fernández hand-made dozens of tiles from clay and soil that are placed on the floor in front of the bricks. On each tile is etched the name of a company that profits from the carceral system such as through prison labor or surveillance systems. Museum-goers will walk on top of the tiles, which, as they break and grind down, will create dust that will settle into the plants.

“I’m thinking about what can grow again after things get destroyed and the cycles of destruction,” she said.

“For something to be constructed, something gets destroyed.”